Published research

We have over 140 peer-reviewed research publications, many of which focused on twin pregnancies.

We have over 140 peer-reviewed research publications, many of which focused on twin pregnancies.

By conducting significant research, the Twins Research Centre aims to translate knowledge into practice. This will ultimately result in better care and improved health for twin infants and their mothers.

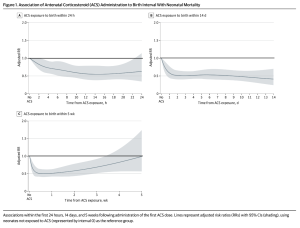

Babies born very early (before 32 weeks of pregnancy) are at high risk of serious health problems, but we know that giving antenatal corticosteroids (ACS)—a medication that helps mature the baby’s lungs—can greatly reduce these risks. Current guidelines suggest giving ACS when early delivery is expected within the next 7 days, however, it is unclear how soon the medication starts working or how long the benefits last, especially for twins. We found that ACS begins to help as early as 2 hours after the first dose, and that the best outcomes are seen when ACS is administered between 12 hours and 14 days before birth. The benefits remained for up to 4 weeks but gradually decreased over time. These results were consistent for both singleton and twin babies. This study shows that giving steroids is worthwhile even when birth may happen very soon.

The figure above shows some of the graphs from our paper. On the vertical axis is the adjusted relative risk (RR), this is a ratio of the probability of neonatal mortality in babies that received ACS and those that didn’t. If the RR is above 1.0 then neonatal mortality is more likely to occur in the babies that received ACS. An RR below 1.0 means that neonatal mortality is less likely to occur with ACS administration. Adjusted means that confounding variables, or those that may affect the results, were removed. The shaded grey area are the 95% confidence intervals, or the range at which the true relative risk can fall within, at each time point. The RR is significant if the confidence interval does not include 1.0.

The graphs, therefore, show that neonatal mortality is reduced with ACS as soon as 2 hours after administration, and that the greatest effect is between 12 hours and 14 days (graphs A and B). After 14 days, the benefit begins to decrease, with it disappearing at 4 weeks after administration (graph C).

Twin pregnancies have higher rates of preterm birth. It has been questioned whether twin babies born preterm are at a greater risk of long-term neurodevelopmental complications compared with singleton babies born at the same gestational age. This question is of major importance, especially at very early gestational weeks (such as 24-26 weeks), where this information may affect parental counseling and guide management decisions, such as the threshold for active management (i.e., providing resuscitation and treatment to the very premature baby). However, data on this topic are limited. In this study, we addressed this question using a large national database that contains information on the early-childhood outcomes of a large number of singleton and twin babies born between 23-28 weeks of gestation in Canada. Overall, we found that among babies born extremely early (23-26 weeks), twins had a greater risk of early-childhood complications than singleton babies. However, these differences were mostly limited to twin pregnancies with certain complications of monochorionic twin pregnancies (i.e., twins who share a single placenta) and do not apply to otherwise uncomplicated twin pregnancies. This means that twin babies born extremely premature, in the absence of complications related to monochorionic twin pregnancies, should undergo the same counseling and management as that of singleton pregnancies at the same gestational age.

There is much uncertainty regarding the best ways to decrease the risk of preterm birth in twins, and guidelines published by different professional societies often provide conflicting recommendations. In the current study, we surveyed maternal-fetal medicine specialists across Canada. We found that there are differences between specialists regarding how twin pregnancies are managed by individual specialists, including recommendations for physical activity in pregnancy, monitoring of cervical length, and the use of cervical suture (cerclage) or progesterone in women with a short cervix. We recommended that efforts should be made to standardize recommendations for the prevention of preterm birth in twins.

It is unclear whether delivering twins preterm increases a mother’s risk of having another preterm birth in their next singleton pregnancy. Using data from 2 large tertiary centers in Toronto (Sunnybrook and Mount Sinai Hospital), we found that a previous preterm birth in a twin pregnancy increases the risk of preterm birth in a future singleton pregnancy, and that this risk is also related to how preterm the twins were.

There is uncertainty regarding the risk of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies following a preterm twin birth. We reviewed all of the published scientific papers that studied pregnancies with a previous twin birth followed by a singleton pregnancy. We pooled the results of these studies together, and found that if an individual delivers twins preterm, they have a higher risk of giving birth to their next single baby early. The earlier the preterm twin birth, the higher the odds of the next pregnancy being preterm.

In ‘late-preterm’ (between 34 and 36 weeks) singleton pregnancies, it has been shown that providing antenatal corticosteroids to promote fetal lung maturation is beneficial. However, it has not been investigated in late-preterm twins. Using data from a large, international study, we found that in individuals at risk of delivering their babies late-preterm, the risk of their babies having problems with their lungs is similar to single baby pregnancies. This suggests that care providers who consider corticosteroids during the late-preterm period for singleton pregnancies, may consider extending this practice to late-preterm twins as well.

Sometimes, the cervix in a twin pregnancy dilates too early (25 weeks or less). It is uncertain whether inserting a cervical stitch (otherwise known as a rescue cerclage) versus a wait-and-see method results in better outcomes for the parent and baby. Therefore, we studied the medical records of individuals with twin pregnancies where the cervix was dilated too early in pregnancy. We compared those pregnancies with a cervical stitch inserted and those without. We found that a cervical stitch can prolong pregnancy and improve the outcomes of the babies in individuals with a dilated cervix before 25 weeks, compared to no cervical stitch.

In some pregnancies, the water breaks too early (called preterm premature rupture of membranes, or PPROM). There is uncertainty whether the characteristics of PPROM are different between twin and singleton pregnancies. Therefore, we studied the medical records of twin pregnancies at Sunnybrook, in the case where the water breaks too early. We found that even though the water breaks too early, in twin pregnancies it tends to break a little later compared to singletons. It also is associated with a shorter time between water break and birth. These pregnancies tend to be less likely to experience infections or placental abruption (the placenta peeling off the wall of the uterus) compared to singleton pregnancies.

One way in which preterm birth is predicted is through measuring the length of the cervix via ultrasound. It is uncertain whether multiple measurements taken over the length of a pregnancy can improve the prediction of preterm birth in twins, compared to a single measurement taken in the middle of the pregnancy. Therefore, we studied the medical records of all twin pregnancies at Sunnybrook between 2012 and 2014. We found that taking frequent measurements of the cervix in a systematic way can increase the likelihood of detecting twin pregnancies at risk for preterm birth.

Information about the effects of medications for infant lung maturation is limited in twin pregnancies, due to the small number of people pregnant with twins who enroll in studies related to these medications. Therefore, we studied the medical records of preterm singletons and preterm twins who were admitted to neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) in Canada between 2010 and 2014. We found that giving pregnant people a course of medications called for lung maturation 1-7 days before birth in twins is associated with lowered risk of infant death, lung complications, and severe brain injuries. This is similar to what is found in single babies.

Women with a twin pregnancy are at increased risk for preterm birth and measuring the length of the cervix via ultrasound is a powerful way to predict it. Obstetricians frequently monitor cervical length in multiple gestations; yet, the optimal method to use the results of cervical length measurements has not been determined. Therefore, we studied the medical records of all individuals with twins at Sunnybrook between 2012-2014. We found that there are 4 patterns of shortening of the cervix, and each has a different risk for preterm birth.

The risk of preterm birth increases with more fetuses in the womb (twins, triplets etc.) However, it is uncertain whether there is a different rate at which the cervix shortens in twins versus triplet pregnancies. Therefore, we studied the medical records of twin and triplet pregnancies that underwent length measurements of the cervix from 16-32 weeks of pregnancy. We found that triplet pregnancies are associated with a faster cervical shortening and higher rate of preterm birth compared to twin pregnancies.

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (P-PROM) is associated with poorer outcomes for babies. It is not clear how to manage mothers who experience P-PROM very early in pregnancy (i.e., before 23-24 weeks, known as the ‘pre-viable period’), since these cases carry even greater risks because the baby may be born very early and the lack of fluid so early in pregnancy can affect lung development. We studied the outcomes of mothers of single or twin babies after P-PROM in the pre-viable period (between 20-24 weeks) who chose to continue with pregnancy. We found that nearly half (49%) of the babies survived, but the babies who survived and their mothers were at risk of serious poor outcomes. This study emphasized the need for individualized counseling to mothers with pre-viable P-PROM and for close surveillance at a tertiary pregnancy center.

One challenge in managing preterm labour (PTL) is classifying true and false preterm labour – less than 15% of those who present in PTL will deliver within 7 days of presentation. To predict preterm delivery, cervical length screening is used, however there is only limited information regarding the accuracy of cervical length screening in twin pregnancies that present in threatened PTL. In this study, we compared the accuracy of cervical length screening in twin pregnancies with PTL to those with singleton pregnancies. The key findings are that in women with PTL, the performance of cervical length screening as a test for the prediction of preterm delivery is similar in twin and singleton pregnancies. However, the optimal threshold of CL for the prediction of preterm delivery appears to be higher in twin pregnancies, mainly owing to the higher baseline risk for preterm delivery in these pregnancies.

One challenge in managing preterm labour (PTL) is classifying true and false preterm labour – less than 15% of those who present in PTL will deliver within 7 days of presentation. To predict preterm delivery, cervical length screening is used, however there is only limited information regarding the accuracy of cervical length screening in twin pregnancies that present in threatened PTL. In this study, we compared the accuracy of cervical length screening in twin pregnancies with PTL to those with singleton pregnancies. The key findings are that in women with PTL, the performance of cervical length screening as a test for the prediction of preterm delivery is similar in twin and singleton pregnancies. However, the optimal threshold of CL for the prediction of preterm delivery appears to be higher in twin pregnancies, mainly owing to the higher baseline risk for preterm delivery in these pregnancies.

Pregnant women with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at high risk of complications, including the development of preeclampsia. However, diagnosing preeclampsia in this population is challenging, as many of its typical signs—such as high blood pressure and proteinuria (protein in the urine)—are often present before pregnancy in patients with CKD. This study is one of the largest to examine pregnant women with CKD, and demonstrates that a new test, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio assay, can aid in the accurate diagnosis of preeclampsia.

Sunnybrook is the first center in Ontario to implement this assay, which measures the levels of two proteins—sFlt-1 (soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1) and PlGF (placental growth factor)—that influence blood vessel development. In the Twins Clinic, we also use this specialized test in mothers with twin pregnancies suspected of having preeclampsia (with or without CKD), to help confirm or rule out this important diagnosis.

Although dichorionic twin pregnancies have separate placentas, the two placentas may fuse together if implanted near each other. Studies describing the outcomes of these pregnancies are conflicting. Therefore, we aimed to compare the outcomes of dichorionic twin pregnancies with fused versus separate placentas. We found that twins from pregnancies with fused placentas were more likely to be smaller (or growth restricted). At the same time, mothers with fused placentas had a lower risk of developing preeclampsia. Our findings can be used to predict and counsel on pregnancy complications in dichorionic twin pregnancies, if placentas are found to be fused during ultrasound.

Mothers with single pregnancies who have hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), such as preeclampsia, are at risk of future cardiovascular disease. Given the possible differences in the mechanism underlying HDP in twin pregnancies compared with singleton ones, it’s not clear if this association between HDP and future maternal cardiovascular disease is true in twin pregnancies. In agreement with our hypothesis, we found that twin mothers with HDP had lower risk of future cardiovascular disease than singleton mothers with HDP. Still, both types of mothers had a higher risk than those without HDP. These findings provide some reassurance to mothers with twins who experienced HDP.

It is unclear whether the outcomes of twin pregnancies complicated by hypertension and preeclampsia differ compared to singleton pregnancies. In this paper we compared singleton and twin data from BORN (Better Outcomes Registry & Network Ontario). The key findings of this paper show that although the risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes is higher in twin compared with singleton pregnancies complicated by hypertension and preeclampsia, these findings may be related to the higher baseline risk of some of these outcomes in twin pregnancies compared to singleton pregnancies.

In singleton pregnancies there is a strong association between high blood pressure in pregnancy and fetal growth restriction. However, it is unclear whether this association is also present in twin pregnancies given the different mechanisms of high blood pressure and fetal growth restriction in twins compared with singletons. To address this question we reviewed the records of twin and singleton pregnancies from Sunnybrook. We found that the association between these 2 conditions in twin pregnancies is similar to that in singletons ONLY when the diagnosis of fetal growth restriction in twins is done using twin-specific growth charts. Our findings suggest that the use of a twin-specific growth chart (rather than the same growth charts used in singleton pregnancies) should be used to diagnose fetal growth restriction in twin pregnancies.

In singleton mothers, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), such as preeclampsia, are thought to be caused by an abnormal placental function, most commonly due to insufficient blood supply to the placenta. This placental disease, which is called maternal vascular malperfusion (MVM), can be identified on a pathological examination of the placenta under a microscope after birth. In an attempt to better understand the mechanisms of HDP in twin pregnancies, we compared the placentas of mothers who experienced HDP in twin vs. singleton pregnancies. We found that placentas from mothers with HDP in a twin pregnancy were less likely to be small and have MVMs than those from mothers with HDP in a singleton pregnancy. These findings provide support to our hypothesis that HDP in twin mothers may be caused by different factors than in singleton mothers.

In twin pregnancies, a significant difference in size between the two babies—called intertwin size discordance—can increase the risk of complications and influence decisions about how and when to deliver. We often use ultrasound measurements late in pregnancy to estimate the babies’ sizes and check for discordance, but it hasn’t been clear how accurate these estimates are. In this study, we compared the accuracy of two ultrasound measurements in predicting actual birthweight differences, and their ability to identify selective fetal growth restriction (where one twin grows significantly slower than the other): 1. estimated fetal weight (EFW) and 2. abdominal circumference (AC). We found that EFW-based discordance was more accurate than AC-based discordance in estimating the true size difference at birth. However, both methods had limited ability to correctly diagnose large birthweight discordance and selective fetal growth restriction (sFGR). These findings show that while ultrasound is a helpful tool, it has limitations, and that obstetricians should use ultrasound results carefully and consider other clinical factors before intervening based on suspected growth discordance alone.

Twin babies tend to grow more slowly than singletons in the third trimester, and when using singleton growth charts to track twin pregnancies, many twins (up to 50%) are labeled as having fetal growth restriction (FGR). However, it is unclear if twins truly have FGR or whether their smaller size reflects normal adaptation to avoid overstretching the uterus. In this editorial, we reviewed new research that helps us better understand why twins grow differently. Our findings strengthened the idea that twin-specific growth charts should be used instead of singleton charts , to avoid overdiagnosing growth problems in twin pregnancies and reduce unnecessary interventions.

Twins are known to grow slower than single babies in the third trimester. However, it remains unclear whether the slower growth represents a pathology (i.e., intrauterine growth restriction from a failure of the placenta to support two babies) or normal benign adaptation in an attempt to decrease uterine stretching (and thereby decrease the risk of preterm birth). One important implication of this question relates to the type of growth charts that should be used to monitor the growth of twin babies during pregnancy: if the slower growth represents pathology, it would be preferable to use a singleton growth chart to identify these small babies who might be at risk. If, however, the relative smallness of twins results from benign adaptive mechanisms, it is preferable to use twin-specific charts to avoid overdiagnosis of intrauterine growth restriction in twin pregnancies. We found that the use of twin-specific charts can reduce the number of twin fetuses wrongly diagnosed with intrauterine growth restriction by up to 8-fold. They can also lead to a true diagnosis of intrauterine growth restriction that is more clinically relevant to identify twins who are at risk of complications due to placental insufficiency.

Twin fetuses face an increased risk of suboptimal growth and fetal growth restriction. One of the measures that aids clinicians in identifying twin fetuses that might be affected by such suboptimal growth is the difference in the size of the 2 co-twins, known as the intertwin size discordance (and is calculated as the difference in the weight of the 2 twins, divided by the weight of the larger twin, and expressed as %). However, there is an ongoing debate regarding the threshold of size difference that should raise a concern. While some studies suggested that the size discordance is concerning only when it exceeds 20-25%, others suggested that even smaller differences may be indicative of suboptimal growth of the smaller twin. In the current study we attempted to answer this question using a novel approach. We identified the threshold of intertwin size discordance that is associated with suboptimal growth by examining the placentas of the smaller twins for evidence of placental insufficiency. Based on this unique approach, we found discordant growth in dichorionic twins should raise the concern of fetal growth restriction of the smaller twin only when the discordance is greater than 25%.

When twins are different sizes in the womb, this can be a risk factor for negative pregnancy outcomes. However, it is unclear whether the timing of the size difference and how fast the twins grow differently may affect the prognosis of the pregnancy. Therefore, we studied the medical records of all twin pregnancies at Sunnybrook between 2011 and 2020. We found that there are 4 distinct growth patterns among twins that are related to adverse outcomes. Multiple measurements seemed to be more informative than a single measurement of size difference.

Fetal Growth Restriction (FGR) is defined as the failure of a fetus to reach its growth potential due to a pathological factor (most commonly, dysfunction of the placenta). FGR is a serious complication and can cause stillbirth, neonatal death, and short- and long-term complications. This study, performed through the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics), brought together worldwide leading experts to summarize the evidence-based recommendations evidence for how to diagnose and manage FGR, as well as indicates areas where research is needed to provide further recommendations. This article attempts to take into consideration the unique aspects of antenatal care in low-resource settings, through collaboration with authors and FIGO member societies from low-resource settings such as India, Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.

Monochorionic diamniotic twins (babies that are identical and share a placenta but have two separate amniotic sacs) are at risk of several serious complications, one of which is selective fetal growth restriction (sFGR), where one of the babies is considerably smaller of the other. sFGR is classified into three types, of which type-III is the most severe and unpredictable type, where the smaller twin is at risk of sudden demise. The goal of this study (1/3 in a series of studies on this topic) was to describe and quantify the risk of fetal demise in these cases. The overall rate of fetal demise was 8.2%. The risk decreased with gestational age: it was 8.1% before 16 weeks, which decreased to <2% after 28 weeks, and to <1% after 33 weeks. In most cases, delivery was scheduled for 32 weeks.

It is uncertain whether the slowing of growth of twins observed in the womb during the third trimester is a normal physiologic adaptation or an abnormality reflecting failure of the placenta to support 2 babies. We used data of all twin pregnancies born in Sunnybrook. We discovered that twin fetus growth slows down at around 26 weeks of pregnancy, and that some body parts such as the abdomen are affected more than others.

In twin pregnancies, the second twin (i.e., the one located higher in the uterus, further away from the cervix) is known to be smaller and to have a higher risk of complications compared with the first twin (known as the presenting twin). The reasons for this are still unclear. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that this is due to the poorer function of the second twin’s placenta compared to that of the first twin. We studied a large number of dichorionic twins (twins who have two separate placentas) and found, in agreement with our hypothesis, that the placentas of the smaller twins were also smaller and were more likely to show signs of insufficient blood flow than the placentas of the first twin. We speculated that this is due to the higher location of the second twin and their placenta, which is further away from the main blood supply of the uterus.

It has been found that twin fetuses grow slower during the third trimester compared with single-fetuses. However, it is unclear whether the smallness of twin fetuses is due to factors related to the placenta, which is the case when singleton growth is restricted in the womb. Therefore, we studied the medical records of the smallest babies born at Sunnybrook (both twins and single babies) between 2002 and 2015. We compared twins to singletons and looked at the difference between negative outcomes in these groups. We discovered that what makes a baby grow slowly in a twin pregnancy may be different from what does this in a singleton pregnancy and may suggest that smallness in a twin pregnancy is not as serious as smallness in a single baby pregnancy.

It is uncertain whether there is a relationship between the sex of the fetuses and the outcome of the pregnancy in twin pregnancies. Therefore, we studied all twin pregnancies with babies in separate amniotic sacs between 1995-2006. We compared the outcomes of pregnancies with male-male twins, male-female twins, and female-female twin pairs. We found pregnancies with a female co-twin had better outcomes than those with a male co-twin.

The accuracy of ultrasounds to estimate fetal weight in twins that are growth restricted is unclear, as the formulas used to estimate fetal growth are based on singleton pregnancies. In this paper we compared ultrasounds performed on twin pregnancies to those performed on singleton pregnancies. We then analyzed both the whole group and only those with fetal growth restriction or major size differences between twins. The key finding of this paper is that the accuracy of the ultrasonographic estimated fetal weight seems to be lower for twin gestations than for singleton gestations, especially for second twins. These data should be considered by clinicians when making decisions based on ultrasonographic characteristics.

Excessive or insufficient maternal weight gain during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of pregnancy complications. In twin pregnancies, there are higher nutritional demands, and so insufficient weight gain can lead to even higher rates of complications, especially preterm birth. However, there is no current standardized protocol to guide, monitor, and manage weight gain in twin pregnancies. In this study, we investigated a new care pathway involving a week-specific weight gain chart and a standardized management care pathway. The care pathway included education for both mothers and care providers, a stepwise management plan for mothers with insufficient weight gain, and referrals to a dietician in some cases. We found that mothers exposed to the new carepathway were more likely to achieve optimal gestational weight gain and less likely to experience insufficient weight gain compared with those not exposed to the new care pathway. Our study showed that this simple, low-cost, and easily implemented intervention can potentially improve outcomes for mothers of twin pregnancies.

Excessive or insufficient maternal weight gain during pregnancy is associated with poorer outcomes. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines for maternal gestational weight gain (GWG) provide detailed recommendations for GWG in singleton pregnancies, but provide only provisional recommendations for twin pregnancies, partly due to the challenge in interpreting studies on GWG in twins. One challenge is the fact that GWG is dependent on the duration of gestation, so studies must account for this factor, given the high rate of preterm births in twin pregnancies. In this study, we reviewed 19 studies on GWG in twin pregnancies published between 1990 to 2020. We found that 56.8% of women experienced inappropriate weight gain, either insufficient (35.4%) or excessive (21.4%). Insufficient weight gain was associated with an increased risk of preterm birth before 32 weeks and a decreased risk of preeclampsia. Excessive weight gain was associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia. Given that over half of twin mothers experienced inappropriate weight gain (which is associated with preterm birth and other poor outcomes), weight gain is an important modifiable risk factor in these pregnancies.

Excessive or insufficient maternal weight gain during pregnancy is associated with poorer outcomes. Current Institute of Medicine guidelines for twin pregnancy weight management have insufficient evidence to make detailed recommendations, despite the fact that such recommendations are especially important for twin pregnancies given the higher risk for preterm birth and other complications. Our study aimed to identify the optimal range of weight gain in twin pregnancies and to estimate the association between inappropriate weight gain and pregnancy complciations, by studying a large number of twin pregnancies at our centre between 2000 and 2014. We found that 30% of mothers gained weight below, and 17% gained weight above current guidelines. For mothers in the ‘normal weight’ category, insufficient weight gain was associated with the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight. Excessive weight gain was associated with a higher risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (such as pre-eclampsia), but associated with a lower risk of low birth weight. We concluded that inappropriate weight gain is an important modifiable risk factor in twin pregnancies, and that there is a need for better guidance regarding optimal weight gain in twin pregnancies.

Peer-reviewed, scientific research papers about the optimal weight gain in twin pregnancies are limited. As a result, the international organizations that defines optimal weight gain in pregnancy (the Institute of Medicine) has only published interim recommendations for twins. Therefore, we aimed to identify the optimal range of weight gain in twin pregnancies. We studied the medical records of all twin pregnancies followed at Sunnybrook between 2000 and 2014. We studied the weight gain of twin pregnancies that had positive outcomes, and found that this weight gain was similar to the recommendations from the Institute of Medicine, except for those who were classified with an obese pre-pregnancy body mass index. For this group, our data showed a lower optimal weight gain range. Also, we found weight gain outside of recommendations was associated with negative outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight, and preeclampsia.

In singleton pregnancies, maternal body mass index (BMI) has been shown to be related to the risk of pregnancies complications. However, it remains unclear whether this relationship is also present in twins given the higher baseline risk of many of these complications in twins. Using provincial data from Ontario, we discovered that being classified as underweight (low BMI) during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of preterm birth especially in twin pregnancies. At the same time, we found that the association of obesity with pregnancy complications is weaker in twin pregnancies than in singleton pregnancies.

Even if a mother intends to try for vaginal delivery, there is a risk for intrapartum caesarean section (c-section or CS), where CS is performed unexpectedly during labour due to failure of the labour to progress or due to distress of one or both twins. Most studies on the risk of CS in twin pregnancies have focused primarily on the risk of an emergency c-section of the second twin (after the first twin was born vaginally). However, data on the overall risk of intrapartum c-section for any reason, even before the first twin is born, are limited. In the current study, we found that twin pregnancies are associated with a greater risk of intrapartum c-section compared to singleton pregnancies. This finding may be due to suboptimal contractions of the overdistended and overstretched uterus, which increases the risk of poor labour progression. This study provides helpful information that can be valuable when counseling mothers on their individualized risk of intrapartum c-section and in making decisions about mode of delivery.

One of the controversies in twin pregnancies is related to the mode of delivery, specifically, whether planned cesarean delivery (CD) is safer than a trial of vaginal delivery. An important factor for counseling around delivery is the risk of needing an urgentintrapartum (during labour) CD. However, data on the likelihood of a needed intrapartum CD in twin pregnancies are limitd. We used a large data set (from the Twin Birth Study) to develop an online toolto predict the risk of intrapartum CD in twin pregnancies. We found that the overall rate of intrapartum CD was 25.4%, and CD for the second twin (after the first twin was born vaginally) was 5.7%. The main risk factors for an urgent intrapartum CD were: nulliparity (i.e., first birth), giving birth after 37 weeks, a noncephalic (i.e., head not down) presentation of the second twin, a history of CD in a prior pregnancy, and labor induction. Our prediction models were confirmed to be accurate and may assist care providers in counseling mothers regarding the optimal mode of delivery in twin pregnancies.

One of the controversies in twin pregnancies is related to the mode of delivery, specifically, whether planned cesarean delivery (CD) is safer than a trial of vaginal delivery (VD). A large study, the Twin Birth Study, found no differences in severe poor outcomes regardless of mode of delivery. However, they did not report on differences in milder complications in the babies or mothers. Using the same dataset, we found no differences in overall mild respiratory or neurologic complications between a planned CD and a trial of VD. However, we did find that a planned CD was associated with a lower risk of several complications including a low Apgar score, needing assisted ventilation (help with breathing) within the first 24 hours of delivery, low-grade intraventricular hemorrhage (bleeding into the ventricles in the baby’s brain), and abnormal umbilical cord gases (pH <7.0) compared with a trial of vaginal delivery. Our study can help with counseling mothers with twins mon the optimal mode of delivery.

A decision to undergo a trial of labor after a previous c-section (TOLAC) should carefully consider the risk of complications (including the risk of rupture of the uterine scar), as well as the chance of success. Previous studies have shown that outcomes in twin and singleton mothers and their babies are similar after TOLAC. However, those studies did not consider the presentation of the second twin (i.e., whether the second twin is head down or not). In the current study we aimed to compare mother and baby outcomes in twin TOLACs depending on whether the second twin was head down or not. A successful TOLAC occurred in 81.5% of cases where the second twin was head down compared with 76.6% when it was not. Rates of complications in mothers and babies were similar between both pregnancy groups. Therefore, we concluded that TOLAC is an acceptable mode of delivery, if desired, even in mothers where the second twin is not head down.

There is often a need to induce labour in twin pregnancies for maternal or fetal reasons (i.e., hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (like pre-eclampsia) and fetal growth restriction). The success rates and safety of labour induction may be different in twin pregnancies than in singleton pregnancies. In this review, we summarized the incidence, success rate, safety, and methods for labour induction in twins, which may help healthcare providers in counseling mothers with twin pregnancies.

Whether twins should be born vaginally or via cesarean section has been the subject of debate over many years. The Twin Birth Study (TBS), a large, randomized controlled trial provided the groundwork for evidence-based recommendations, though further questions were left out of the scope of this study. The current recommendations are:

In cases of twins born very early in gestation, there is a concern that a vaginal delivery may be associated with an increased risk of birth trauma to the second twin, especially when the second twin is in breech presentation. We studied all very preterm twins born before 28 between 2010 and 2017 in level-3 NICUs across Canada. We found that in cases where the first twin was facing head-down but the second twin was breech, there was no difference in risk of negative outcomes for the babies if the patient has a vaginal birth or a cesarean birth. However, we found that nearly a third of the women who had a trial of vaginal delivery required urgent cesarean section for the second baby.

There is limited information about the recommended way to deliver monochorionic-diamniotic twins (twins that share a placenta). We used data collected from a large, international study comparing vaginal birth to cesarean birth in twin pregnancies. We concluded that in individuals with monochorionic twin pregnancies between 32 and 39 weeks, if the first baby is in head-down position, a planned cesarean birth does not raise or lower the risk of serious illness or death of the babies compared with vaginal birth.

There has been uncertainty regarding whether an induction of labour or a planned cesarean delivery has better outcomes for the mother and baby. We used data collected from a large, international study comparing vaginal birth to cesarean birth in twin pregnancies. We concluded that in individuals with twin pregnancies between 32 and 39 weeks, both induction of labour and cesarean section prior to labour have similar outcomes for the health of the baby.

It is uncertain how often a ‘combined twin delivery’ occurs (a birth in which the first twin is delivered vaginally and the second is delivered via emergency cesarean section). It is also uncertain what the risk factors and outcomes for this type of delivery are. Therefore, we used data collected from a large, international study comparing vaginal birth to cesarean birth in twin pregnancies. We found that if the second twin is lying sideways in the womb after the first twin has been delivered vaginally, this is a risk factor for the need to perform an emergency cesarean section for the second twin. When there is a need for a cesarean section for the second twin, this carries a higher risk of negative outcomes for the second baby.

It is uncertain what the outcomes are of cesarean versus vaginal birth in twin pregnancies where patients arrive at the Birthing Unit in spontaneous labour. Using data from a large, international study, we found that in individuals with twin pregnancies who arrive to the Labour & Delivery department in active labour between 32 and 39 weeks of pregnancy, if the first twin is in head-down position, either a planned vaginal birth or planned cesarean birth are associated with similar outcomes.

In a twin pregnancy, the twins are labelled “presenting” and “non-presenting” depending on their position in the womb. The “presenting” twin is lower down than the “non-presenting” twin, and is usually delivered first. In some cases, however, the non-presenting twin is delivered first. It is unclear how often this happens, and what the risks are for this event happening. Therefore, we studied all twins born between 2002 and 2016 at Sunnybrook where one twin was female and the other male. We wanted to study whether the twins ‘switched places’ between the time of ultrasound 2 weeks prior to birth and at the birth itself. We found in 6.8% of births, the twins switched places and the second twin was delivered first.

Sometimes during delivery, there are tears in the anal opening, called “obstetric anal sphincter injuries” or OASIS. The risk factors for these injuries are uncertain in twin pregnancies. Therefore, we studied the medical records of individuals with twin pregnancies who delivered vaginally at Sunnybrook between 2000-2014. We compared individuals who had injuries to their anal opening to those who did not. We found that individuals with twins who had birth assisted by forceps or vacuum were at higher risk of anal injuries.

In some deliveries, there are interventions necessary for the safe delivery of the baby, such as forceps or vacuum extraction. These interventions are more common in vaginal twin deliveries. It is uncertain whether these interventions in twin pregnancies are associated with more injuries to the anal sphincter compared to singleton pregnancies. Therefore, we studied the medical records of individuals with twin and singleton pregnancies who delivered vaginally at Sunnybrook between 2000-2014. We compared the rate of injuries to the anal opening in individuals with twins to those with single baby pregnancies. We found that though individuals with twins required more assistance (with forceps and vacuum), those who had single baby pregnancies experienced more anal opening injuries, mainly due to twin births having earlier delivery.

Sometimes near the end of a pregnancy, one or both twins flip their position from head-down to feet-down or vice-versa. We wanted to look at the likelihood that one of the twins would flip around between the time of ultrasound and the birth. We studied data collected from a large, international study comparing vaginal birth to cesarean birth in twin pregnancies. We found that the likelihood of the lower twin (Twin A) flipping around after 32 weeks is low when they are in the head-down position, but is much higher for the upper twin even in the third trimester.

Gestational diabetes (GDM) is a common complication in pregnancies. There is good evidence that diagnosing and treating GDM improves outcomes in singleton pregnancies, but similar data are not available for twin pregnancies. Twin pregnancies have unique characteristics (such as increased nutritional demands in the presence of two babies), and many of the typical GDM-related complications are less relevant for twin pregnancies. These differences raise the question of whether the greater increase in insulin resistance observed in twin pregnancies should be considered physiological and potentially beneficial (to support the greater nutritional demands of two babies), in which case alternative criteria should be used for the diagnosis of GDM in twin pregnancies. In this review, we summarized the most up-to-date evidence on this topic. We found that mild GDM in twin pregnancies is less likely to be associated with complications than in singleton pregnancies, and may actually reduce the risk for having a small baby (known as intrauterine growth restriction). These findings provide support to the hypothesis that the greater transient increase in insulin resistance observed in twin pregnancies (which is often diagnosed as ‘mild GDM’) is merely a physiological exaggeration of the normal increase in insulin resistance observed in singleton pregnancies (that is meant to support 2 babies), rather than a pathology that requires treatment. These data illustrate the need to develop twin-specific screening and diagnostic criteria for GDM to avoid overdiagnosis of GDM and to reduce the risks associated with overtreatment of mild GDM in twin pregnancies.

Gestational diabetes (GDM) is a common complication in pregnancies. Given the greater nutritional demands in twin pregnancies (due to the presence of two babies), there is a concern that treatment of GDM with strict control of blood sugars (as is done in singleton pregnancies) may not be appropriate for twin pregnancies and might increase the risk of having a small baby (intrauterine growth restriction). In the current study we evaluated 105 twin pregnancies with GDM and found that strict blood sugar control did not improve outcomes and, instead, increased the risk of having a small baby, especially in cases with mild GDM. We concluded that in mothers with twins and mild GDM, caution should be taken not to control blood sugars too strictly, especially when the twin babies are suspected to be small.

Gestational diabetes (GDM) is a common complication in pregnancies, which can result in adverse outcomes like having a large baby, which may in turn increase the risk of complications at the time of delivery.. However, based on the previous work of our group, we found that GDM in twin pregnancies is unlikely to be associated with such complications and that diagnosing GDM in twin pregnancies using the same criteria as in singleton pregnancies might result in overdiagnosis of GDM in twins. In the current study, we compared the accuracy the screening test for GDM (known as the 50g glucose challenge test [GCT]) between twin and singleton pregnancies. We found that the optimal GCT cut-off to identify GDM in twin pregnancies should be higher than the cut-off currently used to identify GDM in twin pregnancies (148 mg/dL vs. 140 mg/dL). These results supported our hypothesis and the need for further studies to determine the best appraoch to diagnose GDM in twin pregnancies.

In this study, we aimed to quantify how at-risk a mother with gestational diabetes was for future type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). We utilized the results from abnormal oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) and the criteria for diagnosis of GDM. The key findings of this study are that the risk of future maternal T2DM increased with the number of abnormal OGTT values and was highest for women with three abnormal values. The risk of future T2DM was also affected by the type of OGTT abnormality. These results may inform providers caring for those with GDM, as individualized information regarding the future risk of T2DM can be provided based on the type and number of abnormal OGTT values, as well as the diagnostic criteria used for the diagnosis of GDM.

The screening approach for gestational diabetes, which is based on a 50g glucose challenge test, has been well validated in singleton pregnancies. Given the physiologic differences and greater increase in insulin resistance in twin pregnancies, the performance of this screening approach in twin pregnancies may differ. In this paper we summarized available literature regarding the performance of the screening test for gestational diabetes in twin pregnancies. The key finding of this paper is that there are no data on how accurate this test is for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes in twins. This means that we do not how many cases of gestational diabetes in twin pregnancies are being missed. Therefore, there is an urgent need to validate current screening approach for gestational diabetes in twin pregnancies. Developing twin-specific 75-g oral glucose tolerance test diagnostic thresholds for gestational diabetes based on the risk of future maternal diabetes: a population-based cohort study.

The current diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes in twins are identical to those used in singleton pregnancies. However, there are considerable in glucose metabolism between twin and singleton pregnancies, one of which relates to the greater need of glucose and other nutrients by the 2 fetuses in cases of twin pregnancies. Therefore, it may well be that different, twin-specific criteria are needed to optimize the diagnosis of gestational diabetes in twin pregnancies, in part to avoid over-diagnosis of gestational diabetes in twins. The current study is the first to develop such twin-specific diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes based on a novel approach and a large provincial dataset. Gestational diabetes and fetal growth in twin compared with singleton pregnancies.

Gestational diabetes is associated with faster growth of the fetus in a singleton pregnancy, but may affect twins differently because they tend to grow slower during the third trimester, and are more likely to be affected by fetal growth restriction. Therefore, we studied all the medical records of twin pregnancies at Sunnybrook between 2011 and 2020. We found that twin pregnancies with gestational diabetes are less likely to be associated with accelerated fetal growth.

In singleton pregnancies, diabetes of pregnancy is associated with a risk of complications. In twins however, it is uncertain whether diabetes of pregnancy carries a similar risk for complications, in part due to the greater demands for glucose in the presence of two babies. We studied all twins and single babies born in Ontario between 2012-2016. We found that gestational diabetes in twin pregnancies was less likely to be associated with high blood pressure issues and certain negative outcomes for the baby, compared to in singleton pregnancies.

It is unclear whether the risk of diabetes of pregnancy, and how often it occurs, differs between singleton and twin pregnancies. We studied the medical records of all people who delivered either a single baby or twins in Ontario between 2012-2016. We found that twin pregnancies carry a higher risk for diabetes during pregnancy compared with singleton pregnancies. However, the effect of known risk factors for diabetes in pregnancy is similar to those who have singleton pregnancies.

Twin pregnancies are at an increased risk for restricted fetal growth in the womb, which may be related to the shared resources by two babies. In addition, gestational diabetes (GDM) can cause accelerated fetal growth, so it is unclear whether this growth may counteract the restricted fetal growth in a twin pregnancy. Therefore, we studied the medical records of individuals with twin pregnancies who were checked in the clinic for gestational diabetes (diabetes of pregnancy) from 2003-2014. We found that there is a relationship between the severity of gestational diabetes and the twins growing to different sizes in the womb.

Considering the differences between twin and singleton pregnancies with regards to weight and level of placental hormones, it is possible that the accuracy of the Glucose Challenge Test (that tests for gestational diabetes) may differ between twins and singletons. In this study, we compared the performance of two glucose tolerance tests (GCT and OGTT) in twin and singleton pregnancies. The main findings of this study are that the 50 g GCT appears to be associated with a higher false positive rate and a lower positive predictive value in twin compared with singleton pregnancies. The screening performance of glucose challenge test for gestational diabetes in twin pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Twin pregnancies are becoming more common, and they come with higher risks for both mothers and babies. While several guidelines exist to help manage these pregnancies, there are still many important questions that remain unanswered. In this review, we summarized the existing evidence in six key areas: prevention of preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, gestational diabetes, gestational weight gain, and the mode and timing of delivery. A main recommendation we make is using several twin-specific tools we developed to help track fetal growth, weight gain, and delivery planning, which are available at https://twincentre.sunnybrook.ca.

Twin pregnancies have higher rates of complications. However, current guidelines on the management of these pregnancies are often inconsistent or have insufficient evidence to support them. In this review, we summarized and compared the recommendations of professional societies related to twin pregnancies. We found considerable disagreement among guidelines, primarily in 4 key areas: screening and prevention of preterm birth, using aspirin to prevent pre-eclampsia, defining fetal growth restriction, and the timing of delivery. In addition, there is limited guidance on several important areas, including the implications of the “vanishing twin” phenomenon, technical aspects and risks of invasive procedures, nutrition and weight gain, physical and sexual activity, the optimal growth chart to be used in twin pregnancies, the diagnosis and management of gestational diabetes mellitus, and intrapartum care. Our summary of key recommendations on twin pregnancies can assist healthcare providers in accessing and comparing recommendations on the management of twin pregnancies and identifies high-priority areas for future research.

In these recent Canadian guidelines, we review evidence-based recommendations for the screening, diagnosis, and management of pregnancies at risk of or affected by fetal growth restriction. Implementation of these guidelines may improve outcomes for mothers and their babies.

In these recent Canadian guidelines, we review evidence-based recommendations for the management of dichorionic (twins who have two separate placentas) pregnancies. Implementation of these guidelines in the care of these pregnancies may improve outcomes for mothers and their babies.

We comprehensively summarized the available evidence for the care of pregnancies at risk of or complicated by fetal growth restriction. This guideline included a specific section dedicated to fetal growth restriction in twin pregnancies. We provided practical recommendations from FIGO (the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) international experts with the hopes of improving outcomes for mothers and their babies. We included recommendations with the unique aspects of antenatal care in low-resource settings in mind, through collaborations with authors and FIGO member societies from low-resource settings such as India, Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.

Maternal age is increasing due to the use of assisted reproductive technologies, and is associated with greater complications. However, it is unclear whether the impact of late maternal age on the risk of these complications, which have been studied in singleton pregnancies, also apply to twin pregnancies. Therefore, we studied a large number (935,378) of women with twin and singleton pregnancies who gave birth in Ontario between 2012 and 2019. Overall, we found that although the absolute rates of pregnancy complications are higher in twin pregnancies, there are considerable differences in the relationship between late maternal age and the risk of certain complications between twin and singleton pregnancies. This information may be relevant for patient counseling and may reassure patients of advanced age with twin pregnancies that their age is unlikely to have a major impact on the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Twin pregnancies have higher rates of complications. Therefore, these pregnancies necessitate closer antenatal surveillance by care providers who are familiar with the specific challenges unique to these pregnancies. In addition, there is evidence that following women with twins in a specialized twin clinic results in better outcomes. In this review, we summarize the available evidence and current guidelines regarding antenatal care in twin pregnancies.We emphasized that the first prenatal visit at an early gestational age is of utmost importance for identifying the number of babies, placentas, and amniotic sacs. At this visit, a follow-up plan should be outlined that focuses on weight gain and level of activity, education regarding the complications specific to twin pregnancies, along with the relevant symptoms and indications to seek care, and close maternal and fetal monitoring.

The loss of a pregnancy is both physically and emotionally taxing on the mother, and can even lead to psychiatric symptoms and disorders. Women may choose to terminate a pregnancy for a variety of reasons, such as genetic or structural abnormalities. In addition, women with twin or triplet pregnancies may choose to reduce the number of fetuses (a procedure known as multifetal reduction) in an attempt to decrease the risk of complications related to twin pregnancies, primarily preterm birth. This may be especially difficult in women who have had a prior pregnancy loss. In the current study, we aimed to understand if the psychological effects of pregnancy termination and multifetal reduction are similar or different, as well as whether a previous pregnancy loss impacts the response to these procedures. We compared two groups of women between 2003 and 2006: those who had a pregnancy termination due to fetal abnormality and those who underwent multifetal reduction to decrease the risk of preterm birth. We found that women from both groups experienced grief and anxiety before and after the procedures, although these feelings were more intense in the termination group on the day of the termination. We also found that anxiety decreased with time in both groups of women. Previous pregnancy loss was not found to affect the emotional response. This study supports the need for continuing psychosocial support of women undergoing pregnancy termination and multifetal reduction.